*This blog post is originally written for and first published on the website of the ARTECHNE project on 3 April 2019.

It has been half a year since I started my PhD project, Everlasting Flowers Between the Pages. The project investigates the epistemic values and the artistic production of seventeenth-century flower books, which are collections of flower or plant watercolors. During this first stage of my research, my major task has been consulting, in person, flower books and other contemporary albums that contain watercolors of flora and fauna in libraries and museums throughout Europe. The hands-on engagement with original albums enables me to not only build my own collection of image data and descriptions, but also my visual and tactile expertise on the materiality of watercolor.

The materials and techniques used by the image makers to create the botanical watercolors are a key focus in my project. To clarify, I do not mean to simply identify that a picture is made with watercolor—in contrast to oil, tempera, or other color media—on paper or parchment. Rather, I aim to analyze, in greater detail, the types of watercolor and painting techniques the image makers applied to visualize plants. Watercolor can be a somewhat fluid term, referring to any water-based paint. Today, transparent watercolor would be what most people immediately associate with when hearing the word; but gouache (or body color)—opaque paint often mixed with chalk—is also a type of watercolor. While today most practitioners tend to specialize in either transparent watercolor or gouache, seventeenth-century image makers often utilized both materials for their works, sometimes even within the same picture plane.

What I look for the most when going through the leaves of a flower book, however, are the traces of steps, techniques, or other issues with materials the image makers might have encountered when painting a flower. This interest in the construction and process of making stems from my own background as an image maker. I was trained as an illustrator for my bachelor’s degree, and built my portfolio with botanical illustrations in transparent watercolor. While I am not a professional practitioner, I have extensive experience with the hands-on aspect of creating a botanical watercolor. From my personal experience, to successfully visualize a plant, it requires both an image maker’s mind to select plant parts and present visual hierarchy, and his/her hand to execute and manipulate the watercolor medium. Thus, details of materials and techniques could help us better understand the practical side of picturing plants in the early modern period.

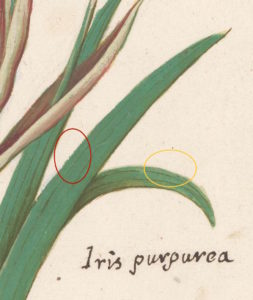

Whilst studying the albums, one recurring detail particularly caught my attention. The Iris purpurea (Fig. 1) in gouache is from a collection of around 750 watercolors of plants and animals, commissioned by Emperor Rudolf II and attributed to Anselmus Boëtius de Boodt (1550–1632) and/or Elias Verhulst (c. 1575–1601), now on long-term loan to the Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam.[1] The ragged edge on the leaf (Fig. 2, dark red oval) is caused by the lack of paint or liquid in a brushstroke. The brush is too dry to give the leaf a smooth finish, like the edge of the leaf to the right (Fig. 2, yellow oval). This kind of coarse edges appear on the majority of watercolors in every album I have consulted for this project. For most modern botanical watercolorists, at least for the school of practitioners that is most active in promoting botanical art today, such brushwork would not be desirable to see in a finished piece. For early modern image makers and viewers, however, this did not seem to pose a problem. Why, then, were these coarse edges so common in early modern botanical watercolors? Could this be a result of the pigments and paints, brushes, and/or painting supports (paper or parchment) that were available in the early modern period?

Fig. 1. Anselmus Boëtius de Boodt and/or Elias Verhulst, Iris purpurea, 1596–1610, watercolor on paper, 22.7 × 15.8 cm, Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam.

Fig. 2. Ragged edge in dark red oval and smooth edge in yellow oval.

The bigger, and perhaps more critical, question behind this observation is why I would even consider the ragged edges a “problem.” Could my training with modern materials, techniques, and aesthetic preference of visualizing plants actually hinder me from objectively studying early modern works because I project too much of my own image-making experience into this research? Moving from making images to studying images, I have seen art historians who over-interpret artworks by disregarding the practical side of artistic production and practitioners who misinterpret the same artworks due to the lack of historical understanding. Neither end of the spectrum is ideal as they provide only one perspective to the whole picture. Thus, how do I effectively apply my practical knowledge without casting my modern bias when studying historical image-making materials and processes?

I think that, as with all good research, the balance can be achieved by remaining aware of the limitation of modern experience in historical interpretation, as well as finding different types of evidence to support observations and answer questions. In the case of understanding why coarse edges so commonly appeared in early modern watercolors, remaking can be a way to provide further insight. Following and experimenting with early modern recipes to make watercolor paints and paint with tools and supports made with historical methods will allow me to see if my attempts resemble any of the visual effects and techniques I have observed in the studied albums. I can also compare my process of working with historical materials to that of working with modern materials to learn if they differ. The samples generated from remaking may not be the most typical kind of evidence for historical research, but they will allow a look into the practical issues image makers potentially dealt with that resulted in the seventeenth-century botanical watercolors being the way they are.

Naturally, it is the responsibility of the maker-historian to have a thorough understanding of historical recipes and documentations, as well as the skills to work with the materials and techniques in such an empirical study. It is, however, not a simple task to master. In a few months, I will officially start undertaking the remaking research for my project, and I look forward to grappling with more issues and challenges that will emerge as I progress as a maker-historian.

[1] A majority of the watercolors from the collection are digitized. For example, see the Iris purpurea in this blog post and other plants in “Album met bloemen” (RP-T-BR-2017-1-9), http://hdl.handle.net/10934/RM0001.COLLECT.664603. For secondary literature on the collection, see exhibition catalogue by Marie-Christiane Maselis, Arnout Balis, and Roger H. Marijnissen, The albums of Anselmus de Boodt (1550-1632): Natural history painting at the court of Rudolph II in Prague (Ramsen: Tenschert, 1999).