*This blog post is originally written and translated for and first published on the blog of the Société bibliographique de France on 21 September 2019.

Nassau Florilegium

The National Library of France (Bibliothèque nationale de France) in Paris houses a codex of 54 gouaches on parchment, usually referred to in French as Le Florilège de Nassau-Idstein (Inv.-Nr. Manuscrit. Rés. Ja-25-Fol) or internationally known as the Nassau Florilegium. Painted by Johann Jakob Walther (or Johann Walter) between 1652 and 1665, the set includes depictions of the Count of Nassau, the castle and garden of Idstein, and the flowers and fruit from the garden.[1] Two European institutions also have similar volumes of the Nassau Florilegium in their collections. The Victoria and Albert Museum in London has 133 flower studies plus several views of the garden that are painted on paper and bound in two volumes (Inv.-Nr. 9174 & 9175) (illustration 1).[2] The Städel Museum in Frankfurt am Main has recently reintroduced to the world their two volumes of the Nassau Florilegium (Inv.-Nr. Bibl. 1596) with 130 gouaches of flowers on parchment.[3]

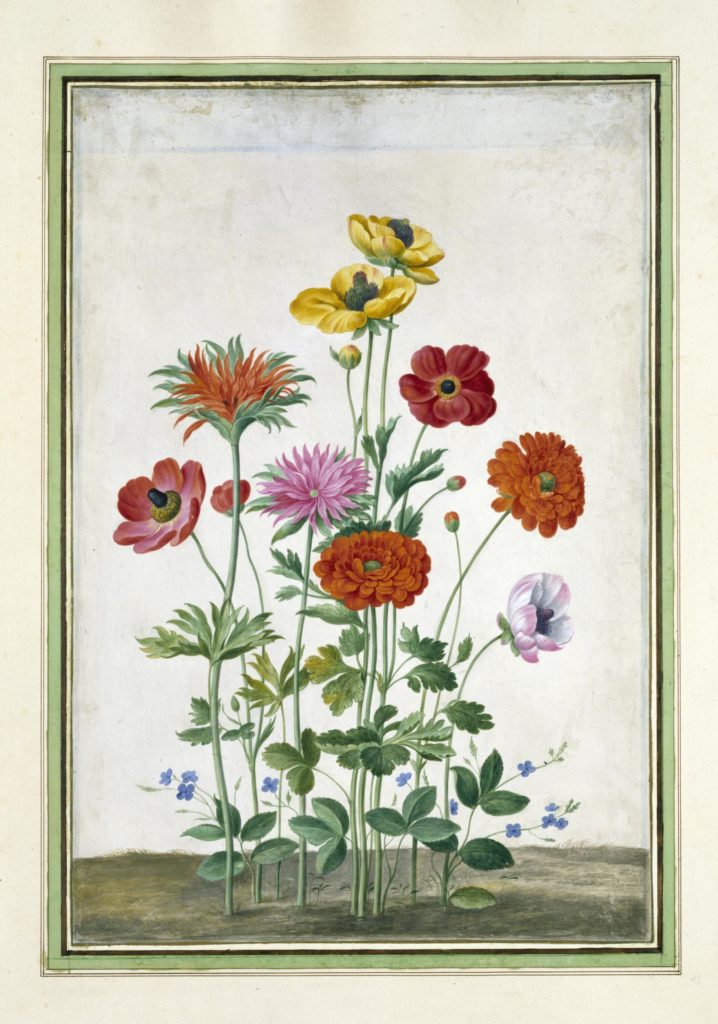

Fig. 1. A flower study from volume 1 of the Nassau Florilegium at the Victoria and Albert Museum (height 600 mm x width 462 mm). Image: © Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

Florilegium as a book genre

The several volumes of the Nassau Florilegium are products of the thriving garden fashion and floriculture in the early modern period, particularly in the seventeenth century. In the most general sense, a florilegium—literally “flower book”—is a collection of flower images. Florilegia are essentially picture books. Copperplate engraving (sometimes hand-colored) and hand-painted gouache/watercolor are two major ways to create images in a florilegium. Text often only appears in the introductory section(s) to state the owner’s possession of the plants and again in the captions for the illustrations. Florilegia of the seventeenth century tend to showcase the blooms of the most valued cultivars, and often feature several color variations of the same flower. Many florilegia, including the Nassau Florilegium, are connected to specific sites once existed, making them a kind of visual catalogue of a garden’s plant collections.[4]

However, the florilegium as a book genre is not as homogenous as described above. This blog post identifies some related issues I have encountered after one year into my PhD research. My project examines the Nassau Florilegium and similar manuscript florilegia as material objects. By closely studying the contents and materials and techniques of a selection of seventeenth-century florilegia in person, I aim to better understand the artistic and knowledge production of this book genre. For example, what does the application of watercolor and gouache in these flower studies tell us about early modern color technology? In addition to their artistic value, do florilegia present any epistemic value in promoting or generating early modern visual plant knowledge?

Issues of intended function and production context

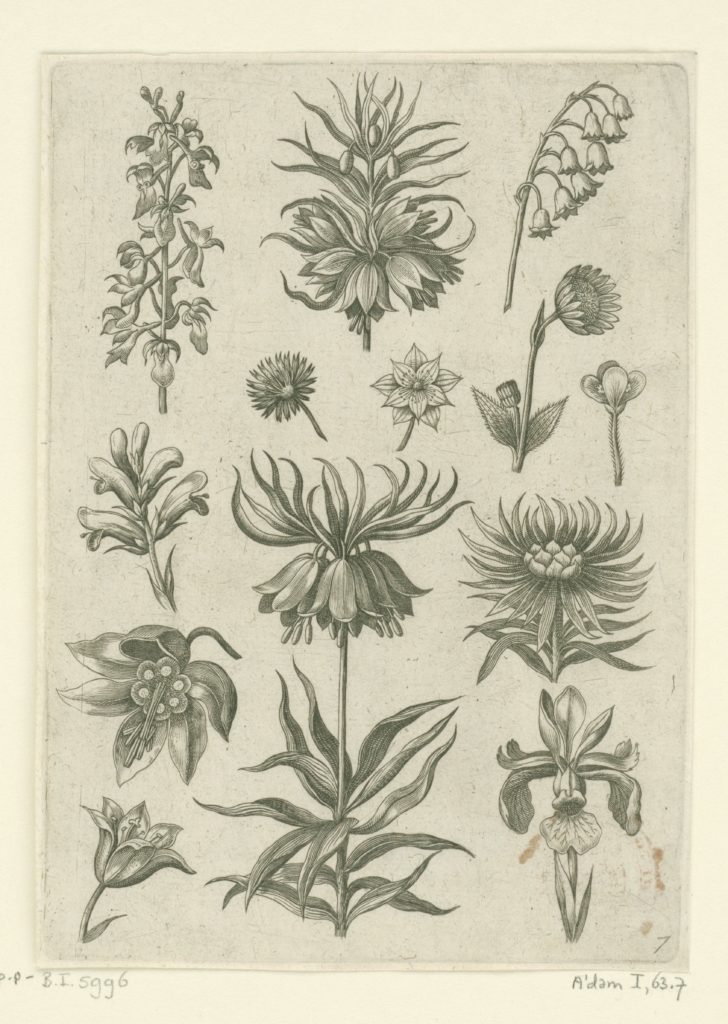

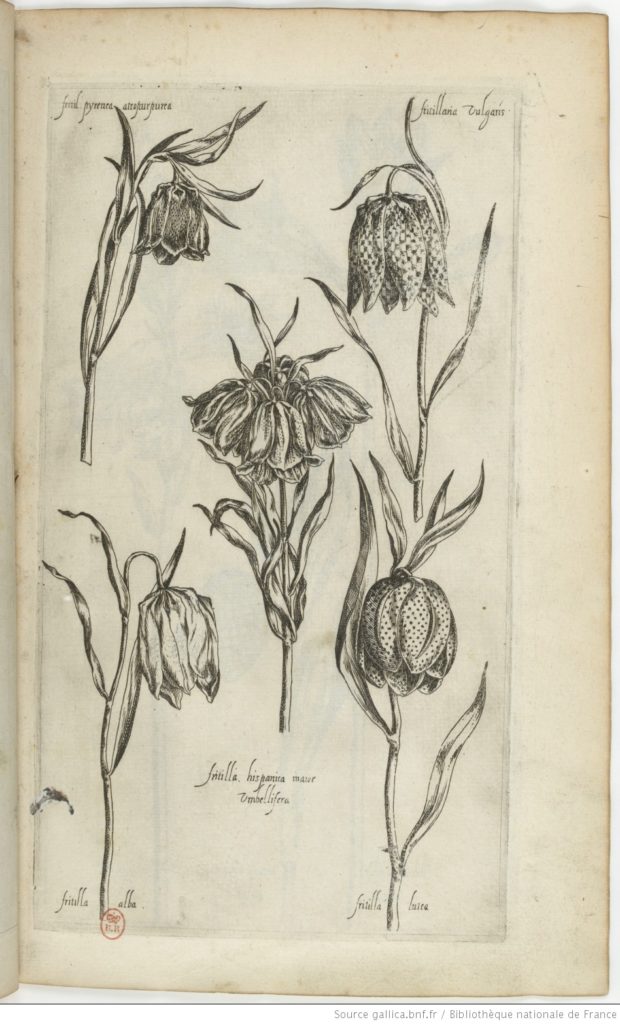

A first step towards eventually answering these questions is to grasp the scope and diversity of seventeenth-century florilegia. The Florilegium (c. 1589) by engraver Adriaen Collaert (illustration 2) is credited as the first to apply the word to mean a collection of flower images.[5] The booklet serves as a pattern book for textiles and other crafts.[6] Thus, even though it is a florilegium as a book of garden flowers, it has a different primary function from the Nassau Florilegium. In 1608, engraver Pierre Vallet published Le Jardin du Roy tres Chrestien Henry IV (illustration 3).[7] The florilegium depicts flowers from the garden of Henry IV, but doubles as a pattern book, as Vallet intentionally designed it for and dedicated it to Marie de Medici and her embroidery circle.[8] One of the most celebrated florilegium is the Hortus Eystettensis (1613) by Basilius Besler (illustration 4).[9] The plants in this sumptuous florilegium were drafted after live specimens gathered from the garden of Bishop Johann Konrad von Gemmingen in Eichstätt, Bavaria.[10] The function of a florilegium serving as a picture catalogue of a garden is thus much more ingrained in Besler’s book.

Fig. 2. A plate from Adriaen Collaert’s florilegium (height 177 mm x width 126 mm). Image: Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam.

Fig. 3. A plate from Pierre Vallet’s florilegium (height 361 mm x width 252 mm). Image: National Library of France, Paris.

Fig. 4. A plate from Basilius Besler’s florilegium (height 55cm). Image: Royal Botanical Gardens, Madrid.

The three printed florilegia show the fluid and flexible nature of the genre. In a way, the Nassau Florilegium is an unambiguous example, despite the fact that many historical details remain unknown and questions related to the surviving volumes remain unanswered. The Nassau Florilegium functions similarly to Besler’s Hortus Eystettensis, but with hand-painted pages instead of engraved plates. It records the plants grown in the garden of the Count of Nassau in Idstein. Correspondences between the Count of Nassau and Johann Jakob Walther indicate that the painter made at least eight trips from his home at Strasbourg to the Count’s estate in Idstein for his work on the flower studies.[11] The Nassau Florilegium, as a whole, has a relatively clear attribution of its painter, patron, and garden. Comparatively, many manuscript florilegia do not have such extensive documentation; this makes it more challenging to learn about their intended functions and production contexts.

Issues of title, description, and content

The Nassau Florilegium is considered one of the top pieces of the genre, making its volumes a regular favorite for exhibitions to include and put on display. There are a number of similar star manuscript florilegia from the seventeenth century, including the Gottorfer Codex (Inv.-Nr. KKSgb2947–KKSgb2950) at the National Gallery of Denmark (Statens Museum for Kunst) in Copenhagen (illustration 5).[12] Beautifully printed facsimiles of these florilegia and reproductions in exhibition catalogues have ensured that researchers and the public alike can admire and study them relatively easily. Florilegia with lesser-known patrons and painters or of lower quality did not share the same accessibility in the past. Fortunately, thanks to the ever-more-completed records for online catalogues and the recent wave of digitizing rare book collections, many institutions have reintroduced some previously more obscure florilegia to modern readers.

Fig. 5. A flower study from the Gottorfer Codex (height 505 mm x width 385 mm). Image: National Gallery of Denmark, Copenhagen.

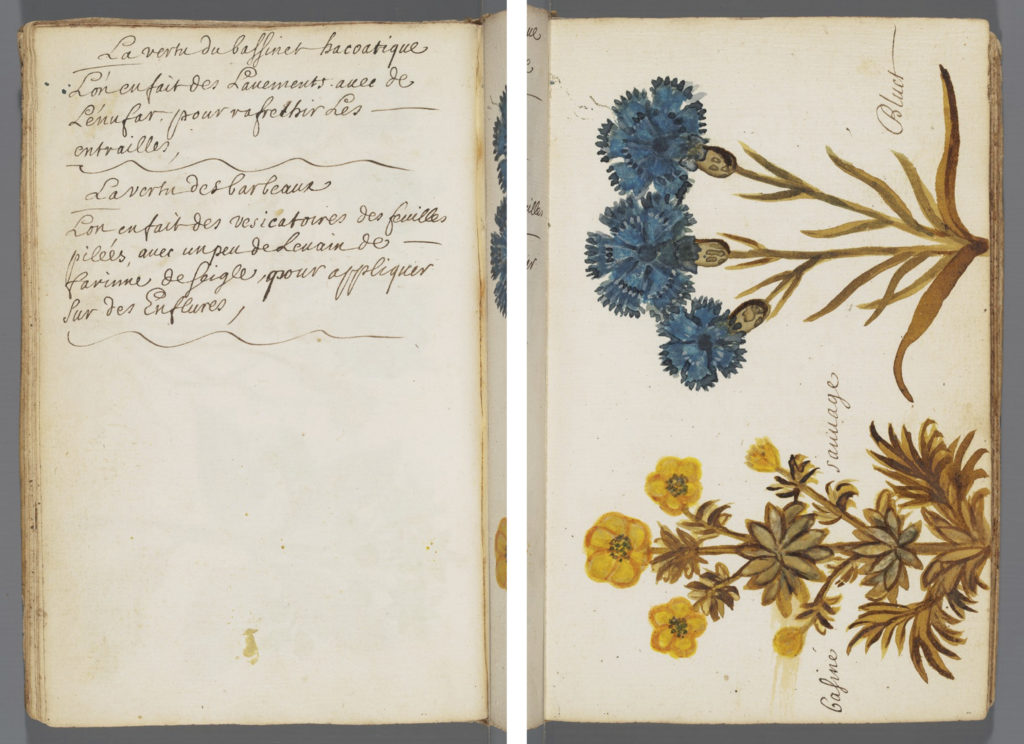

Nonetheless, identifying a potential florilegium in a library or museum collection is not a straightforward task. Printed florilegia usually include the words florilegium or hortus (or instead their vernacular translations) in their titles. Manuscript florilegia, on the other hand, are often untitled and hence rely on descriptions to clarify what they are. In many cases, instead of using the term florilegia, a volume would simply be described as a collection of watercolors/gouaches of plants. Sometimes the description of a volume could read close to a florilegium, but yield to quite different content. For example, a codex at the Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection in Washington, D.C. is now described as a “Collection of seventy-eight water color plates of plants (Inv.-Nr. 014234313)” (illustration 6).[13] When opening the (digitized) book, however, it became clear that the volume is an herbal, describing the medicinal properties of a selection of illustrated plants.

Fig. 6. An example of two descriptions and two illustrations of plants from the “Collection of seventy-eight water color plates of plants” (height 200 mm). Image: Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection, Washington, D.C.

Yet, this kind of neutral description is, in my opinion, a good practice for untitled codices. Oftentimes, a codex containing plant images eludes hard categorization. For example, the Herbarium Danicum sempervivum (Inv.-Nr. GKS 722 folio) at the Royal Danish Library (Det Kongelige Bibliotek) in Copenhagen includes two distinctive parts (illustration 7).[14] The first half belongs more characteristically to the early modern European herbal tradition, featuring medicinal or utilitarian plants with most of their parts (roots, leaves, and flowers) depicted. The second half, however, resembles the content and aesthetic of a florilegium, showcasing blooming tulips, carnations, hyacinths, and other garden flowers in several color variations. This book is both an herbal and a florilegium, and labeling it as only one or the other would limit our understanding of the codex.

Fig. 7. A plant study from the first half (left) and a flower study from the second half (right) of the Herbarium Danicum sempervivum (height 420 mm x width 280 mm). Image: Royal Danish Library, Copenhagen.

Florilegium as a book genre?

The aforementioned issues can be too generalizing and too hair-splitting at the same time. However, as I get to study more codices containing painted flowers and plants, I find it necessary to rethink the definition of the florilegium, and whether it is helpful to approach these collections of plant watercolors/gouaches with a preconceived notion of a book genre. Despite the growing number of volumes I have been able to consult, it became apparent that I am not seeing a full picture of the scope and diversity of surviving works. It is not feasible to travel to even only the major libraries in every European city to examine codices of plant watercolors/gouaches in person; many lesser-known collections might be awaiting to be digitized, or even to be entered and described in catalogues as well.

One of the goals for my PhD research output is to start compiling a list of early modern collections of plant watercolors/gouaches to encourage future research into such materials for any interested person. Thus, this is also a plea to invite curators, librarians, archivists, researchers, or anyone who knows the existence of similar collections of botanical images to send me some information (description, maker, date, inventory number, hosting institution, picture, etc.). A top and well-documented work like the Nassau Florilegium is an excellent starting point to better understand early modern manuscript florilegia. But to gain an even more comprehensive and holistic perspective on these collections of plant watercolors/gouaches requires a collective effort.

[1] For a general introduction to this florilegium, see Laure Beaumont-Maillet, Le Florilège de Nassau-Idstein: Johann Walter (Paris: Bibliothèque nationale de France, 2010).

[2] For a general introduction to this florilegium, see Gill Saunders, Picturing Plants: An Analytical History of Botanical Illustration (London: Zwemmer / Victoria and Albert Museum, 1995), 41; Jenny De Gex, ed., So Many Sweet Flowers: A Seventeenth-Century Florilegium, Paintings by Johann Watther 1654 (London: Pavilion Books, 1997).

[3] For a general introduction to this florilegium, see Jenny Graser and Martin Sonnabend, “Johann Walter der Ältere und das Florilegium des Grafen Johannes von Nassau-ldstein” in Maria Sibylla Merian und die Tradition des Blumenbildes von der Renaissance bis zur Romantik, edited by Magdalena Bushart, Catalina Heroven, Michael Roth, and Martin Sonnabend (Frankfurt am Main and Munich: Staatliche Museen zu Berlin – Preußische Kulturbesitz, Städel Museum / Hirmer Verlag, 2017), 101–115.

[4] For more information on the genre of florilegium, see Saunders, Chapter 2: Florilegia and Pattern Books, 41–64; Claus Nissen, Die botanische Buchillustration: Ihre Geschichte und Bibliographie (Stuttgart: Hiersemann Verlags-Gesellschaft m.b.H., 1951), 66–80; Wilfrid Blunt and William T. Stearn, The Art of Botanical Illustration, reprint edition (Suffolk: ACC Art Books, 2015), 13–14.

[5] Adriaen Collaert, Florilegium (Antwerp: Philips Galle, c. 1589). See digitized copy at https://www.mfah.org/art/detail/124505?returnUrl=%2Fart%2Fsearch%3Fnationality%3DNetherlandish.

[6] Nissen, 68–69.

[7] Pierre Vallet, Le jardin du roy très chrestien Henry IV, Roy de France et de Navarre. Dédié à la Royne (Paris: Pierre Vallet, 1608). See digitized copy at https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b8612033t.

[8] Blunt and Stearn, 99–100.

[9] Basilius Besler, Hortus Eystettensis (Nüremberg: [s.n.], 1613). See digitized copy at https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/creator/94396#/titles.

[10] Nissen, 71–73; Blunt and Stearn, 104–106.

[11] Graser and Sonnabend, 105.

[12] See digitized copies at http://collection.smk.dk/#/en/detail/KKSgb2947.

[13] See digitized copy at https://www.doaks.org/resources/rare-books/collection-of-seventy-eight-water-color-plates-of-plants.

[14] See digitized copy at http://www.kb.dk/manus/vmanus/2011/dec/ha/object84817/en/#kbOSD-0=page:3.